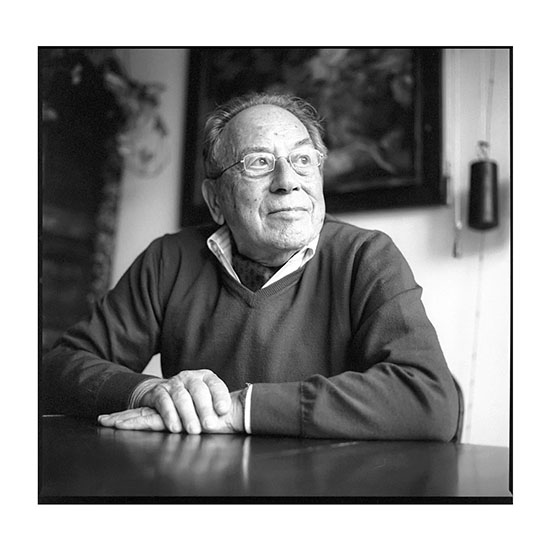

“On the first day of the war there was a big bang- a bomb fell nearby and destroyed the facade in front of our house. I went into the cellar and hid in a baby carriage for all five days of the war. On the last day the Germans bombed Rotterdam. I came out of the cellar and saw that the sky was red because Rotterdam was burning.” -Max van Trommel

The bombing of the Dutch city of Rotterdam by the Luftwaffe occurred on May 14th,1940, four days after the start of the German invasion. The fierce resistance in Rotterdam was to be broken and the Dutch were forced to capitulate. Despite a truce that had been agreed in advance, the city was bombed under circumstances and is still controversial. The historic city center was destroyed, 900 people died and 85,000 people lost their homes. The Dutch government surrendered the following day and thus spared further cities a similar fate. Rotterdam remained occupied until the end of the Second World War.

During the occupation Max’s family suffered under the anti-Jewish measures. Max was the one to bring his sister away to a hiding place and later, he and his brother found a place in different locations in the east of the country. He spent the last three years of the war in hiding.

“During the first year not much changed. Then the Germans ordered us to wear yellow stars on our clothing. I had never been to a synagogue. I didn’t even know I was Jewish until they told me. Laws saying that Jews not allowed to travel on buses and trams, or go to public markets. That was the first serious sign that life had changed. Then they started issuing food coupons. We couldn’t buy certain things because there wasn’t enough food. My mother asked me to go around the city on bicycle to redeem the coupons. That was horrible because I went to shops outside my neighborhood where the owners didn’t know me. When they saw the yellow star they yelled at me to get out. It gave me an awful feeling that I was abnormal and wasn’t a part of the population.

When Jewish families began to be transported, my grandfather said we had to flee. My sister, 4, had to be brought to an address in Den Haag. My mother was unable to do that so I had to. I didn’t know the people who would be caring for my sister. My sister was anxious and felt something was wrong and didn’t want to leave my side. But I had to. The next day, my sister went to play in the garden then I left which was horrible because I betrayed my sister. I always hoped to apologize to my sister at the end of the war. The first time I saw my sister after the war, I spoke to her about it but she didn’t remember. My sister committed suicide at the age of 21. She wrote us a letter saying “I am not normal.” Which we understood because this is how we felt after the war. After the war I discovered my grandparents were hiding close to where I was. They had been betrayed and transported to Sobibor where they were murdered.”

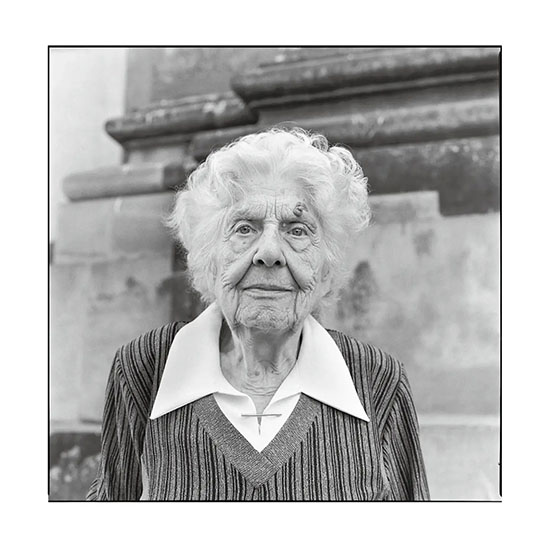

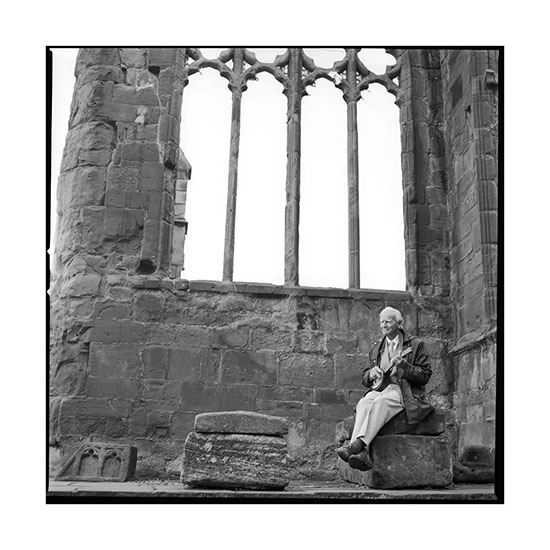

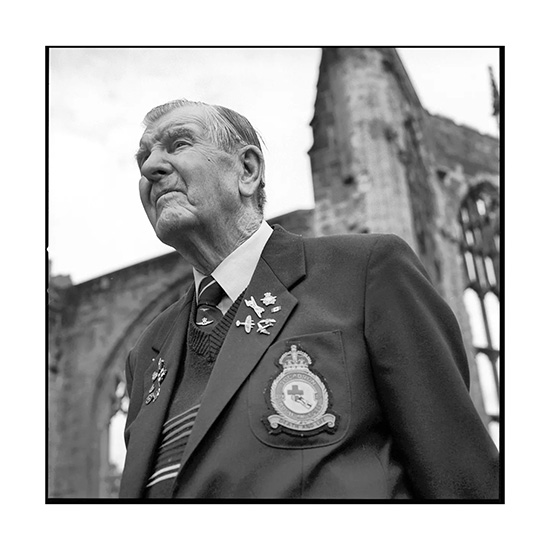

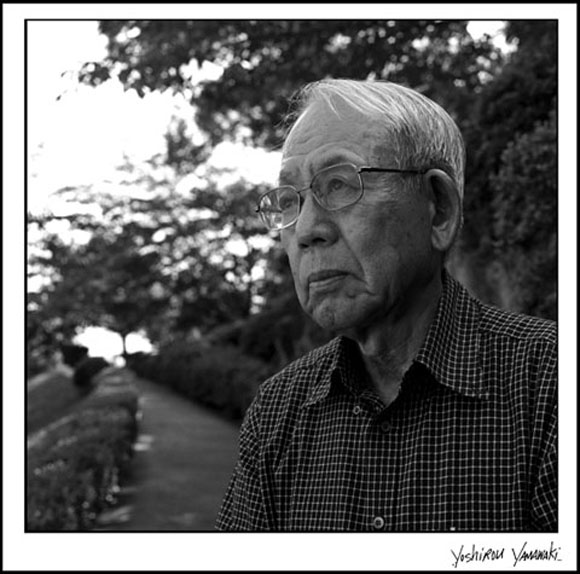

This portrait is a part of my From Above project, which is a collection of portraits and reminiscences of atomic bomb survivors and firebombing survivors from Dresden, Tokyo, Coventry, Rotterdam and Wielun. A portion of From Above is permanently exhibited at the Nagasaki Peace Memorial Hall for Atomic Bomb Victims. It has also been exhibited in numerous museums and exhibition spaces. From Above was released as a limited edition book that was sold at PhotoEye.com. The book is sold out from the site, but I have the last copies. Contact me if you’re interested.